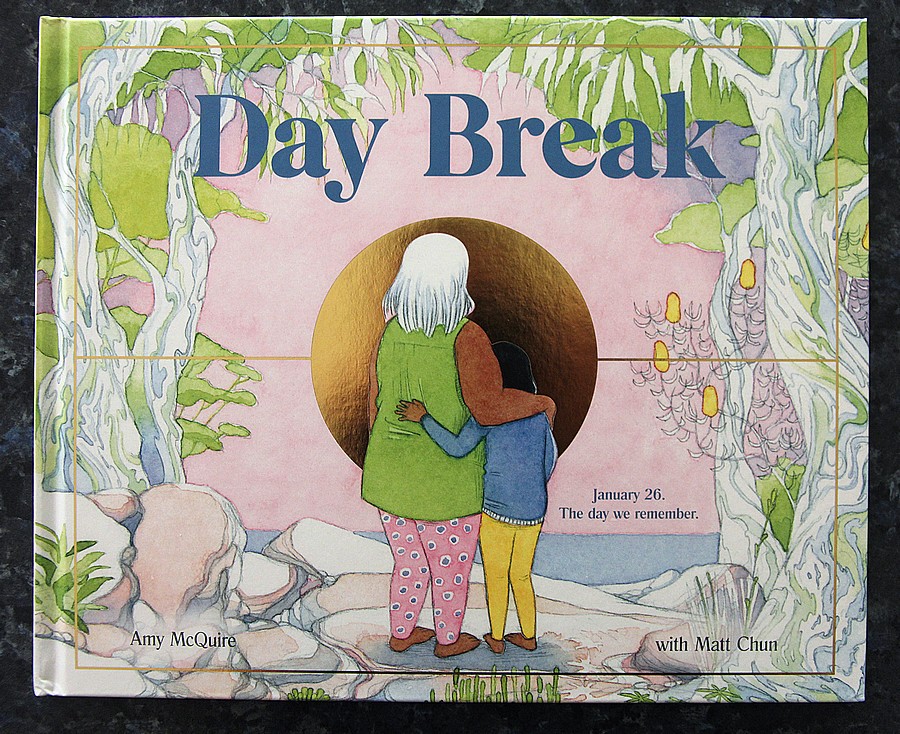

Day Break by Amy McQuire, a Darumbal and South Sea Islander woman from Rockhampton in Central Queensland and illustrated by Matt Chun is a picture book that challenges the narrative around Australia Day and highlights Indigenous survival, resistance and resilience. This powerful and confronting story shares information about Australia’s true history as a family make their way back to Country on January 26. During their journey home, as the family remembers their past and reflects on their current experiences, there are discussions which reveal some of the negative, racist and shameful effects of colonisation and the damaging impacts this continues to have on many Aboriginal people. This book helps children gain a deeper understanding of this contentious date and to us personally was a call to action to ensure we continue to improve our knowledge of Australian history, reflect and remember on January 26. This book explores what Australia Day means for Indigenous families and honours the past while looking to the future.

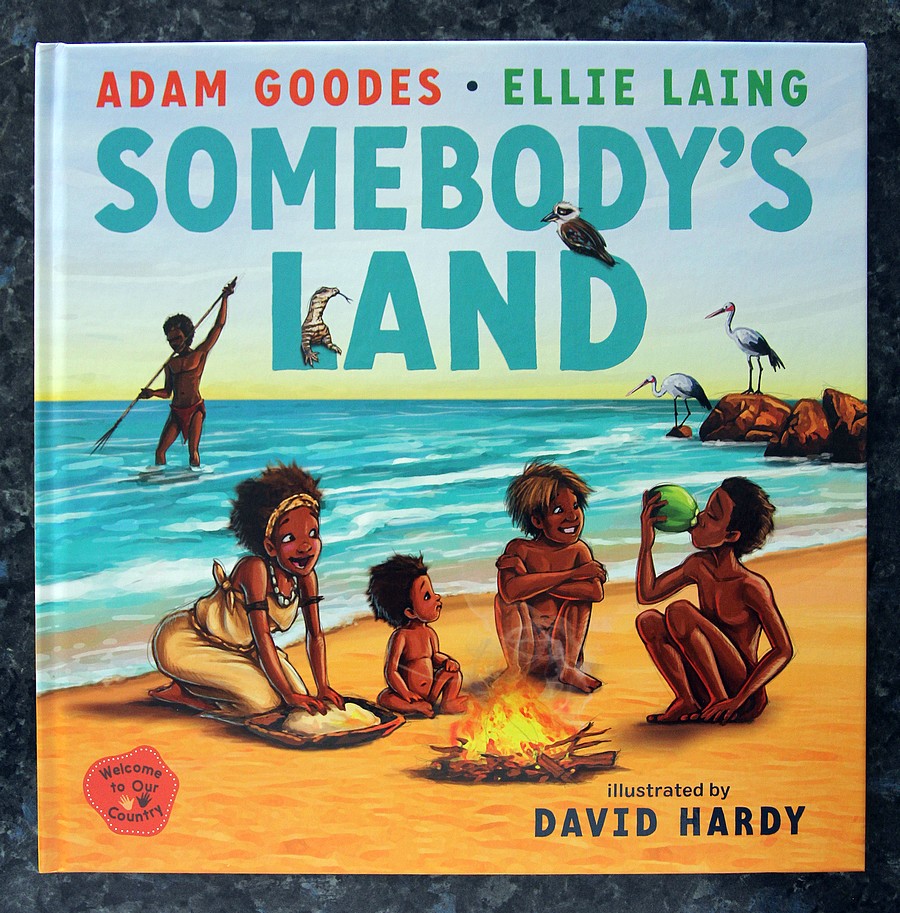

Somebody’s Land: Welcome to Our Country by Adam Goodes, Ellie Laing and illustrated by David Hardy is the first picture book in what is to be a series that will include five books. This is a celebration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, the traditional custodians of the land and the gifts that are their culture, knowledge, stories, practices and deep connection to the land. It is also a story about Australia’s shared history, the injustices and it introduces readers to the term, Terra Nullius which was used by the colonists who arrived on First Nation Country as well as the significance of acknowledging country.

This vibrant picture book explores how Captain Arthur Phillip raised the Union Jack flag, a symbol that the British had arrived and the land was theirs. The Flag was raised on Gadigal land, land that was inhabited by First Nations peoples for at least 60 000 years. No treaty was made with the First Nations peoples then, or since. The Europeans claimed the land was Terra Nullius, a Latin word meaning, “nobody’s land”, but it was somebody’s land.

The book is structured in a way where the words are repeated on each double page spread while showing the rich and diverse ways the Aboriginal people connected with and nurtured the land. The text and glorious illustrations show the Aboriginal people living in harmony and sustainably with the land that was lush, thriving and peaceful. The narrative coupled with the illustrations shows First Nations peoples building homes on the land, telling stories, sustainably sourcing food, being resourceful and inventive with creating tools, tracking animals, enjoying bush tucker and creating medicines from the plants. The story also explores how Aboriginal people shared their teachings. This is ultimately a story to connect past shared history with today’s generation, to start conversations and learn about the culture of the traditional custodians of the land. This book enables readers to see the deep respect and connection to Country First Nations peoples have.

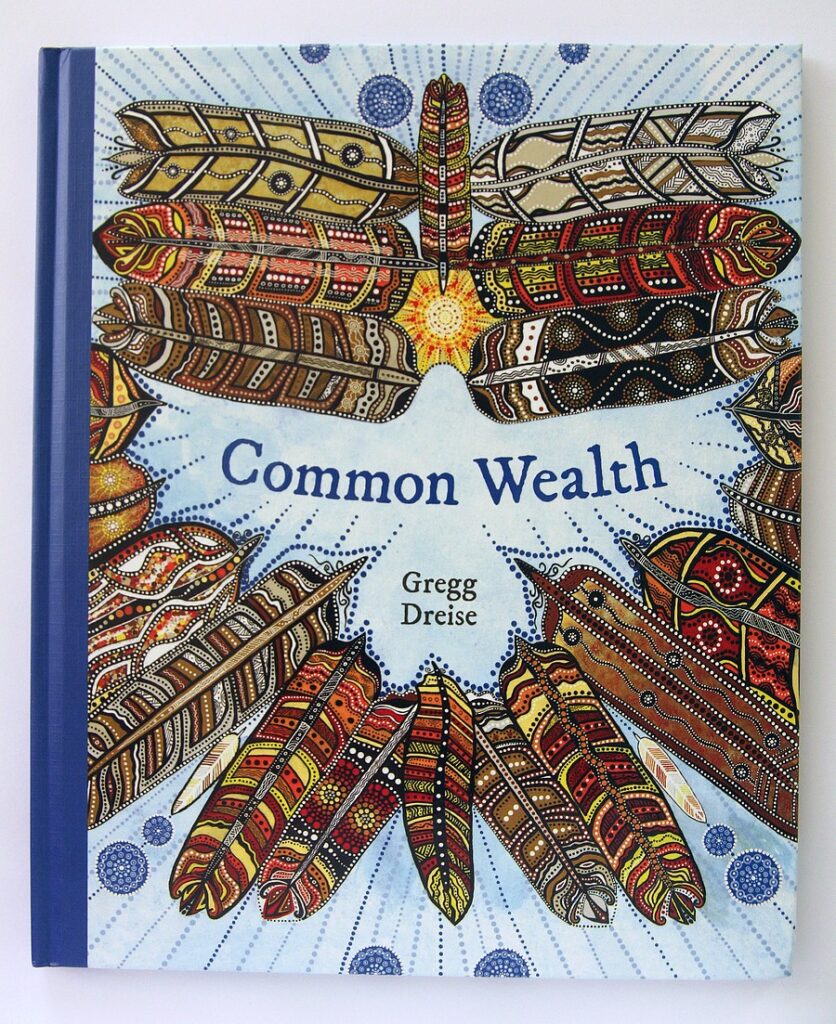

Common Wealth by Gregg Dreise is recommended for older readers (upper primary and secondary school students) as it contains some confronting imagery.

Common Wealth by Gregg Dreise, artist, storyteller, musician and descendant of the Kamilaroi and Euahlayi people of south-west Queensland and north-west New South Wales writes in the style of slam poetry verse, an impassioned plea for unity in this powerful book. He dedicates this book to “all of the people in Australia who are ready for change”. In this compelling, persuasive verse, Gregg Dreise explores Australia’s history, together with Australia’s national anthem, referring to particular lines in the anthem, sharing how are they are not inclusive and he explains what these lines mean to him. There are also calls to action throughout this plea, for example about changing the words “we are young and free“ which does not represent the world’s oldest surviving culture to “proud and free”. At the cornerstone of this heartfelt plea and vision is the necessity for truth; for all Australians to acknowledge and respect the past and recognise that we are all equal, and together, united, sharing a sense of community; we are strong and can achieve great things. The following poignant words are incorporated into one of the arresting illustrations on a double page spread, “grieve together, believe together, achieve together, receive together.” Towards the end of the book, there is another suggestion for moving forward and this is to consider changing the date of Australia Day and a suggested date is given and the reasons why this date is significant. The evocative illustrations add another layer to the powerful words and while some are confronting, so too is Australia’s history and this cannot be ignored. This vision of unity is presented in an accessible way for older readers and the overall feeling of hope permeates throughout this piece as it is a call to unite for the common good. Gregg Dreise masterfully expresses this in a highly engaging, non-didactic and respectful way.

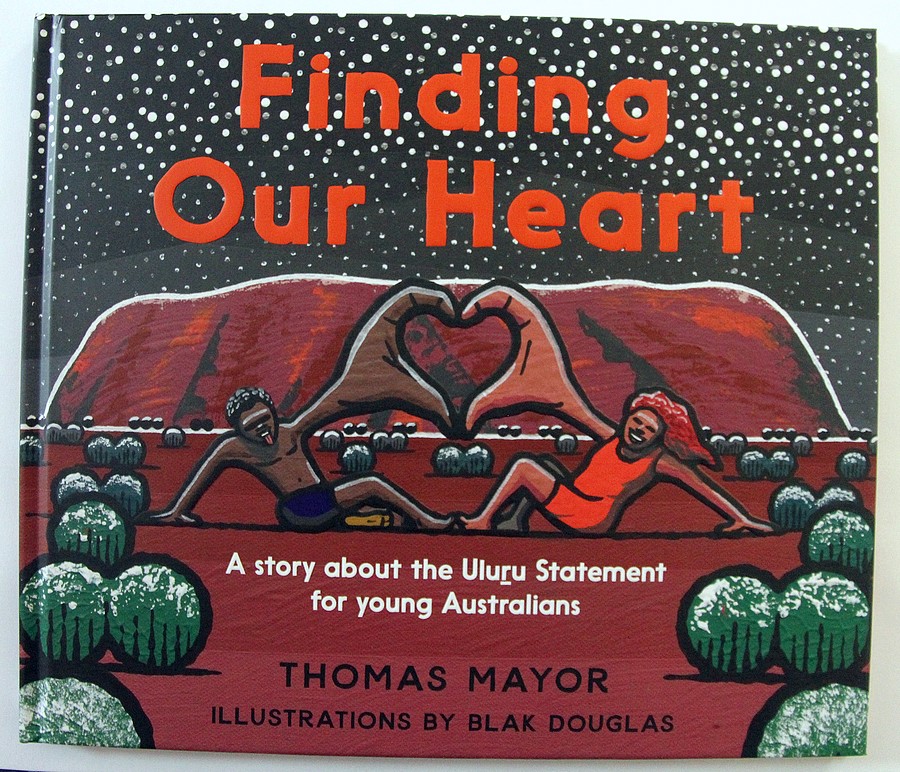

Finding Our Heart: A Story about the Uluru Statement for Young Australians by Thomas Mayer and illustrated by Blak Douglas is a must have book. This book is a call to action as it invites readers to listen and hear the First Nations voices of Australia, the voices that are over 65000 years old. These voices include the languages and the stories that have been passed down from one generation to the next that are filled with culture, knowledge and wisdom. This story invites children to learn the facts about Australia’s history and continue to appreciate Indigenous knowledge and expertise of the land and environment. This book contains the AIATSIS map of Indigenous Australia and the Uluru Statement from the Heart. There are also resources and suggestions at the back of the book for children to support the Uluru Statement. This story highlights that the heart of the nation can be found through the acknowledgement and respect of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture. As the back cover says, this is “a book about understanding Australia’s past, so we can have a shared future”.

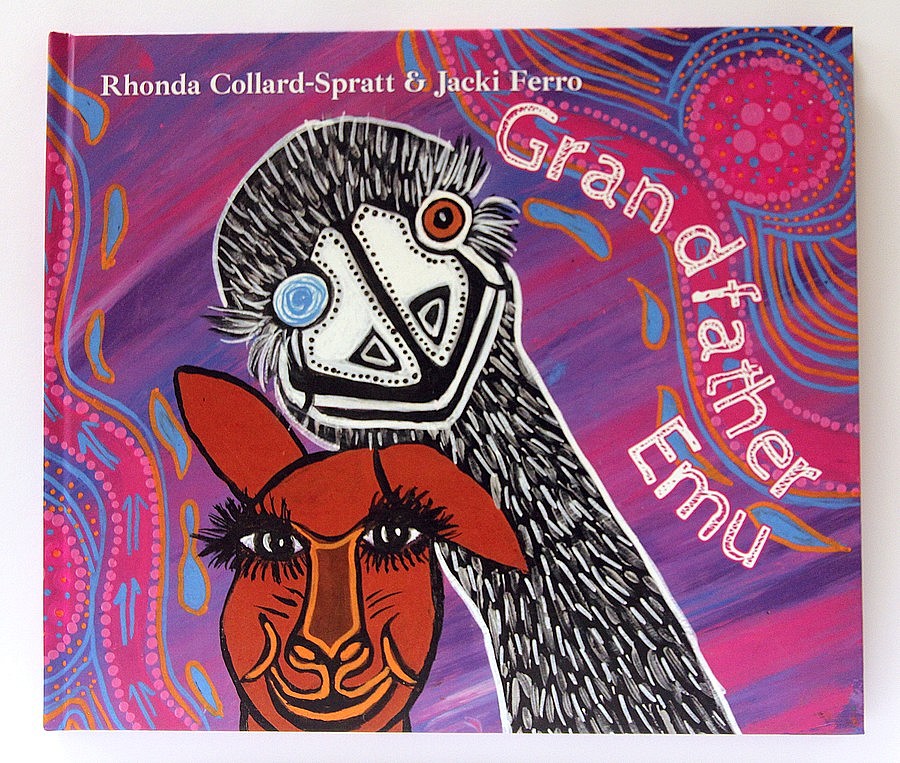

Grandfather Emu and How the Kangaroo got her Pouch is Book 1 in the Spirit of the Dreaming Series by Rhonda Collard-Spratt, a Yamatji-Noongar woman and Jacki Ferro, published by Boolarong Press. This title is the first of a five-part series. At the end of the story it is explained that “the Spirit of the Dreaming series takes Australian Aboriginal Dreamtime stories from the past and creates new Dreamings for future generations”.

In this Aboriginal Dreaming story, a wise Kangaroo talks about The Great Spirit of the Dreaming, the creator of all and the test that The Great Spirit devises for the animals. The Great Spirit transforms into Grandfather Emu. The elderly emu is unable to source water or food and he hobbles along in a desperate attempt to source these. He walks through the bush and encounters several bush animals, Mother Numbat, a crow and a goanna. He asks the animals if they will help him. Each of the animals are distracted with attending to their own needs, so Grandfather Emu grows weaker as he continues to look for water and food without any assistance.

A kangaroo, Mother Yonga, spots Grandfather Emu and asks if she may be of assistance. Mother Yonga compassionately responds to his request and helps him find the creek. Upon learning that the old emu was also hungry, Mother Yonga places her joey in a safe place, away from the threat of harm so that she can continue to help the old emu find food. When Mother Kangaroo returns to the creek, the Great Spirit reveals itself and offers a reward to Mother Kangaroo for being the only animal who helped Grandfather Emu. Mother Kangaroo remains selfless when choosing her reward, one that benefits all female marsupials.

The story is visually driven as vibrant and colourful illustrations illuminate the pages. There are striking images of bush scenes, featuring unique Australian trees such as the Balga trees (grass trees) and flowers. The illustrations include dot painting, patterns and fascinating details to complement the narrative.

This Dreaming Story includes Aboriginal words from the Noongar Language of Western Australia and contains a beautiful lesson about being kind and helping our Elders. It highlights that we are all part of one community and working together, showing compassion and cooperation is vital. Being too busy, apathetic and selflessly driven causes divisions, isolation and unnecessary suffering. Central to the teaching is that we are at our strongest when we help each other and work together.

At the end of the story is a song titled ‘Take the Time To Help’ as well as a list of Aboriginal words from the Noongar Language of Western Australia and their English translations.

This story is also available as an audiobook. The audiobook features Rhonda Collard-Spratt reading the story which transports the reader to the bush as they hear the calls of the different bush animals, the creek flowing, a fire crackling and a didgeridoo playing. This version of the story also allows the readers to hear the pronunciation of Aboriginal words from the Noongar Language of Western Australia that are included in this book.

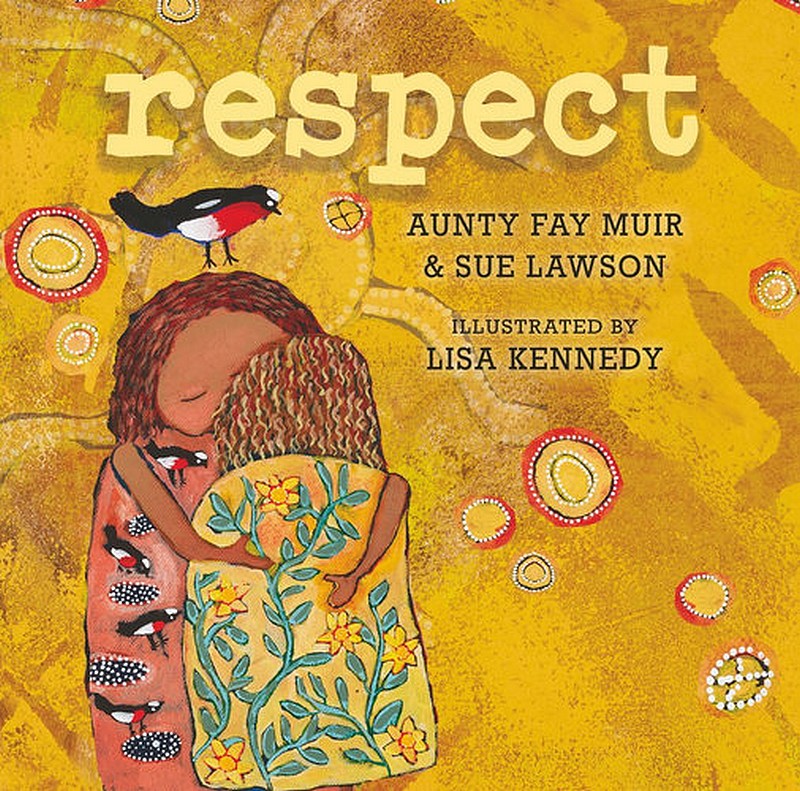

Respect by Aunty Fay Muir, a Boonwurrung Elder and Sue Lawson and illustrated by Lisa Kennedy, a descendant of coastal Trawlwoolway people of north-east Tasmania begins with an elder telling a young child that “our way is old” and “our way is respect”. The reader follows the young child as they learn about respect as a way of life for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples; respect for stories, songs, Elders, Ancestors, the land, family and importantly respecting yourself. The young child learns about the importance of listening to Elders, learning from them and sharing their teachings and lessons. Lisa Kennedy’s vibrant and bold illustrations bring the pared back and powerful text to life.

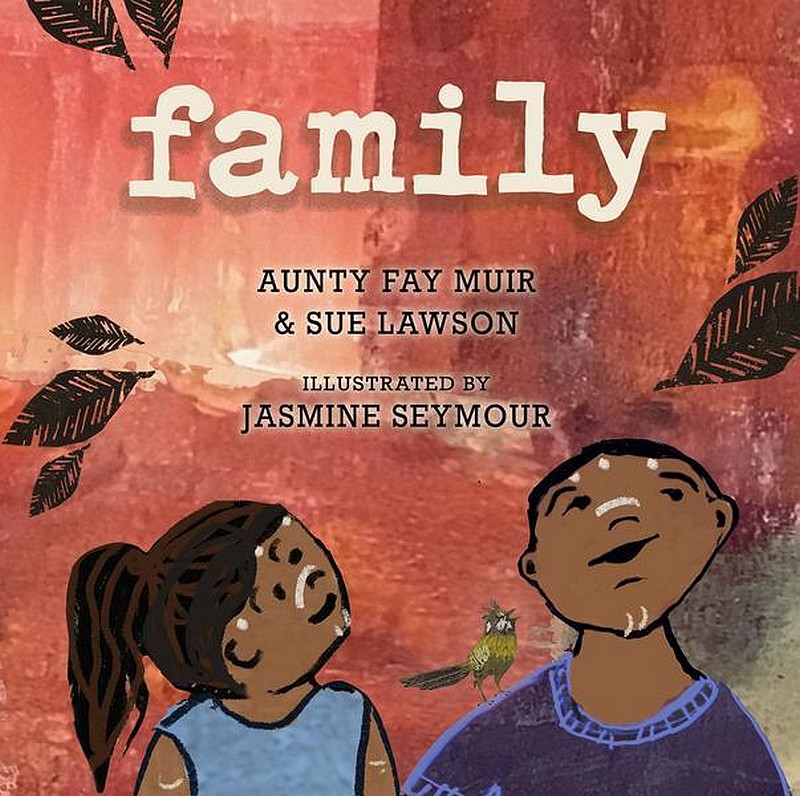

Family by Aunty Fay Muir, a Boonwurrung Elder and Sue Lawson and illustrated by Jasmine Seymour, a member of the Darug people, is a glorious celebration of family and culture highlighting family values, connection, sharing, traditions and belonging. The overall message is that family, regardless of what that looks like, is heart and home to everyone. This is a gentle, accessible introduction to young readers about First Nations culture. Sue Lawson’s warm, rich illustrations created using an earthy toned colour palette add another layer of depth to this book and extend the text. This is the second book from the Our Place series, Respect is the first book.

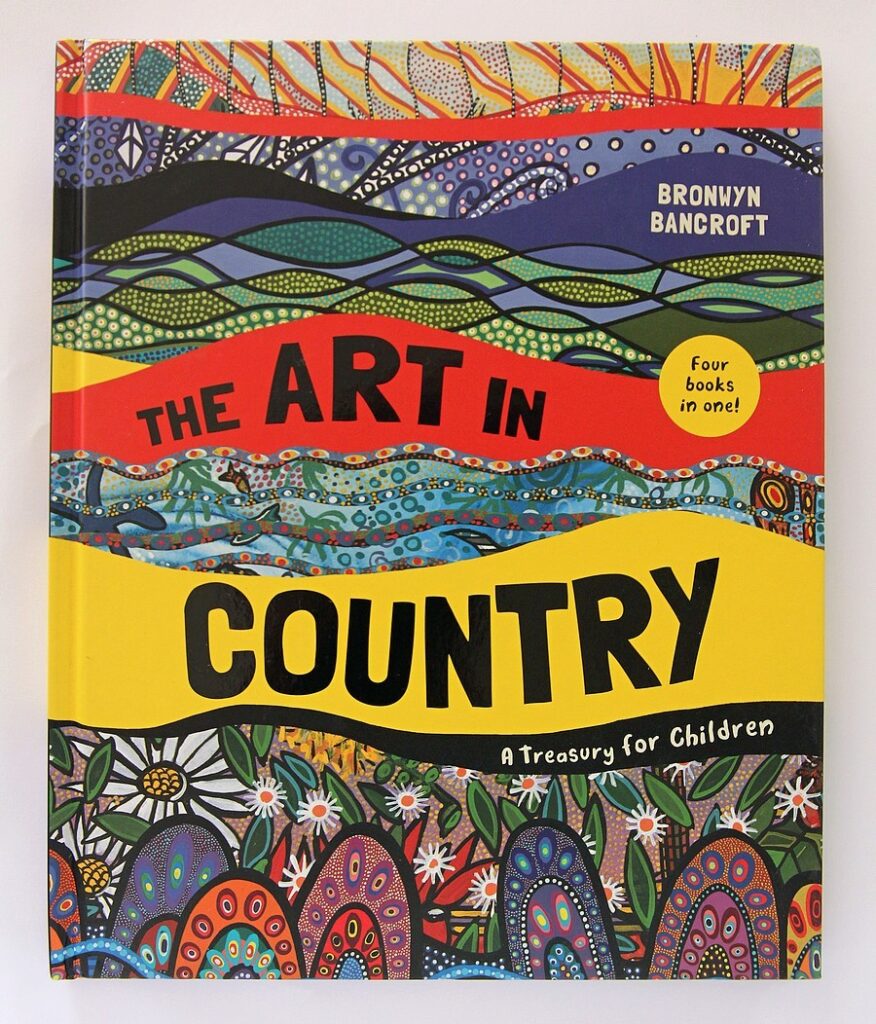

The Art in Country, A Treasury for Children written and illustrated by Bronwyn Bancroft is a glorious celebration of Australia’s wondrous, diverse landscapes and habitats. Colours, shapes, patterns and melodic text are deftly used to bring to life the striking beauty that exists in Australia. The figurative language together with the rich, vibrant illustrations paint vivid pictures of Australia’s stunning beauty as well as its spirit, from “the cloaks of white that drape the rocky crags of snowy mountains” to “shards of rainbow and swaying tentacles of watery light in a coral reef” to more sumptuous descriptions of grasslands, the desert, boab tree families, rivers, and suburbia as well as the modern city lights “like a jewelled necklace”.

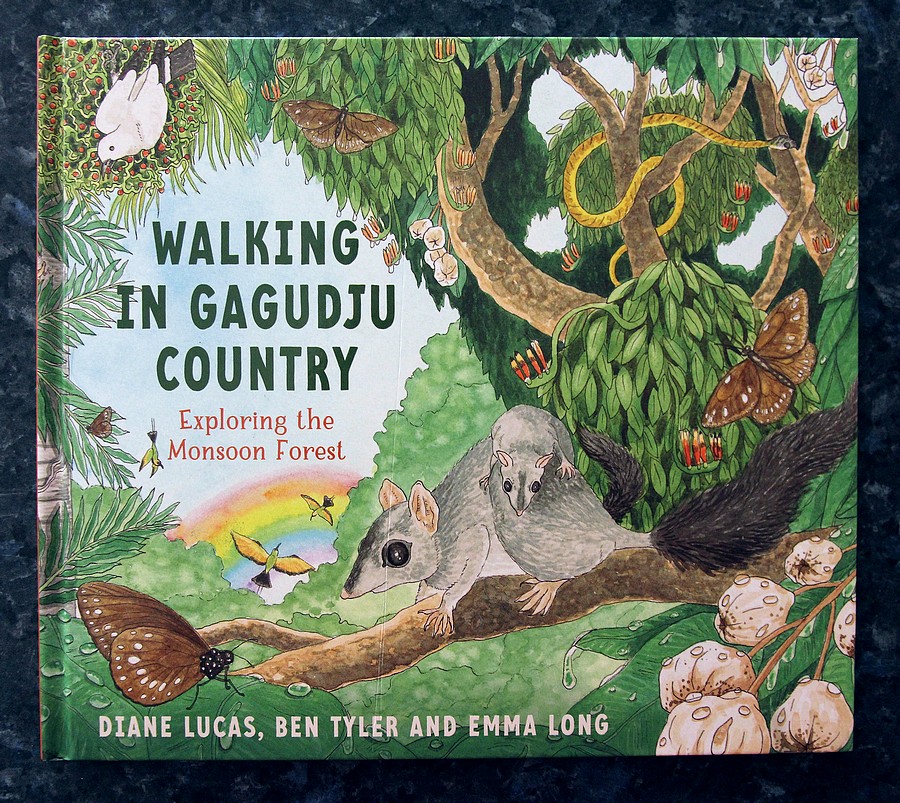

Walking in Gagudju Country : Exploring the Monsoon Forest by Diane Lucas and Ben Tyler, a Bininj entrepreneur and illustrated by Emma Long is a stunning picture book experience that immerses the reader into the richness of the ‘Gagudju’ area. In the notes for readers at the beginning of the book it is stated that another word for ‘Gagudju’ is ‘Kakadu’ and that the monsoon forest in the story is the Kakadu National Park.

This story begins with the enticing premise that walking through country, specifically the shady monsoon forest, means being open to a myriad of possibilities that could be experienced and to be prepared for anything; this adds to the beauty and wonder of the sensory exploration. This story is told in an accessible way using character icons of the authors to share fascinating factual information and wisdom that has been passed on from Aboriginal elders. As the walk begins, remarkable information about animals and plants is shared, as well as where and how to find bush foods. There are numerous stories included that have been passed on from Aboriginal elders, such as one about the Willie Wagtail who calls out to alert people to be aware of the surroundings and possible dangers in the area, for example snakes. This book is brimming with facts, such as details about an ancient tree that can survive fires and cyclones, as well stories and observations, including the meaning of different animal calls, for example, the Mistletoe bird’s call is an indication that the green plums are ready for eating, or other animal calls that relate to the weather. There are interesting facts about the way vines, plants and trees are used to create items such as rafts, canoes, medicines and soap. There are also warnings about which animals to watch out for and others to carefully listen to. The book includes much wisdom from elders about signs to watch for from country and how to interpret what country is alluding to about weather and seasonal changes, such as the blooming of flowers which indicates that it is time to begin burning the woodlands and rock country.

This story embeds the Kundjeyhmi language into the narrative and is done so using colour for the Kundjeyhmi words accompanied by an illustration of the word referred to which is placed near the text. At the back of the book is a glossary with a list of Aboriginal words from the Kundjeyhmi language, their English translations and the page in the story the word appears.

This stunning picture book highlights the riches and beauty that Kakadu has to offer which can be truly appreciated when one keenly observes and listens to the surroundings. Emma Long’s striking, vibrant watercolour illustrations are mesmerising, full of life, movement and illuminate the double page spreads. They include mini scenes that have been extracted from a picture to show remarkable detailing. This is an inspiring story to invite exploration in your own backyard and to listen carefully, watch closely, use your sense of smell, have a curious mind, ask questions and deeply respect country just as Indigenous people have for many thousands of years.

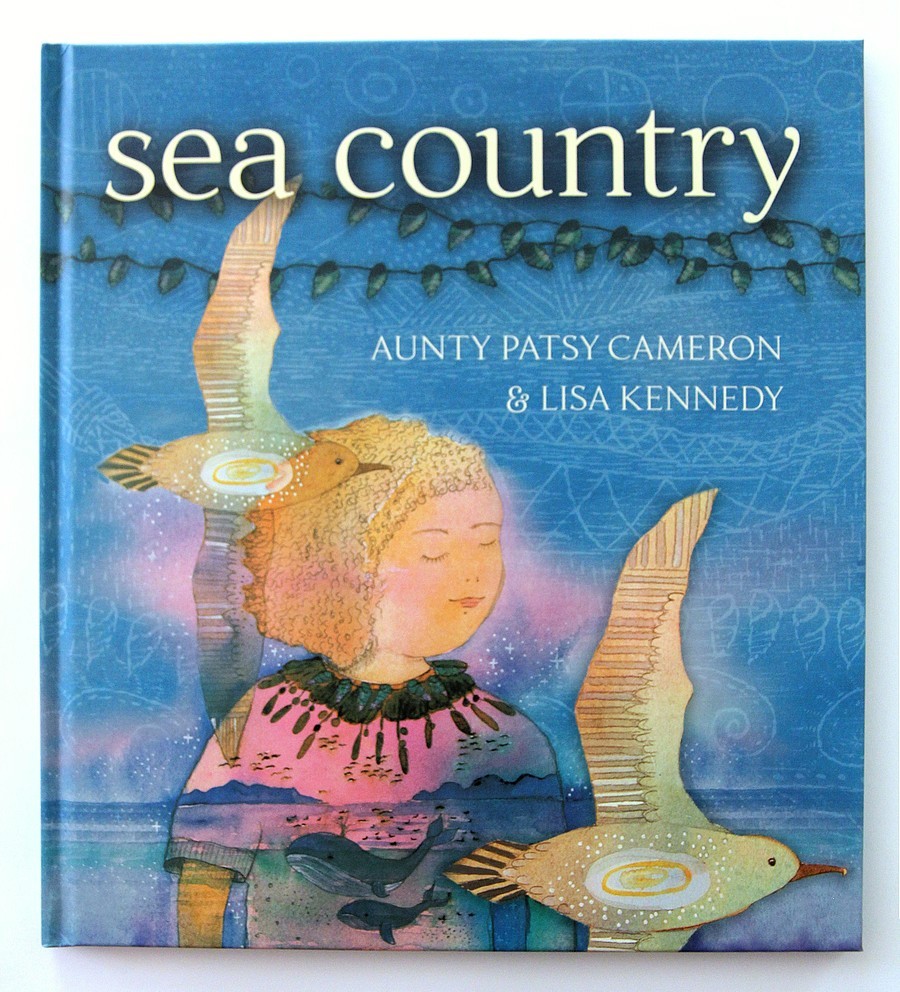

Sea Country by Aunty Patsy Cameron, illustrated by Lisa Kennedy and published by Magabala Books transports the reader back to Aunty Patsy Cameron’s childhood on Flinders Island in eastern Bass Strait. Her carefree days were spent playing on the beautiful beach teeming with fish and searching for treasure in the form of shells; playing with her sister and cousins in glorious caves as well as in the bush, all while discovering and learning about Country from her family and connecting deeply to it. Aunty Patsy’s people are descendants of Mannalaargenna of the Pairrebeenne/Trawlwoolway clan.

When Aunty Patsy was a child she was taught by her Aunties, Uncles, Grandfather and family about Country. Aunty Patsy learnt about foods to eat and she was involved in the seasonal collection of berries and fruits, including wild cherries, tatas and canyon fruits (each of these are beautifully illustrated). She was taught to watch for signs from Country and how to interpret what Country was telling them about weather and seasonal changes, for example, if there was a ring around the moon it was an indication that inclement weather was on its way. The migration of the mutton birds occurred at the same time as the boobyallah flowers erupting; these occurrences were observed and highly anticipated each year. Just as the boobyallah flowers bloom with the arrival of the mutton birds, the nautilus shells would appear with their departure. Aunty Patsy learnt about the many different types of fascinating shells as the women collected them and used these to create beautiful intricate necklaces. There were also certain shells that required specific knowledge to source and this knowledge was passed down from one generation to the next.

Sea Country is a stunning book brimming with vibrant colour, beauty and wonder. Lisa Kennedy’s stunning, evocative, layered illustrations often feature scientific details and the connection Aunty Patsy and her family experienced to Country and in some instances their ancestors. The nuance and intricate details in the mesmerising illustrations are breathtaking. This story is a celebration of the ways in which culture intertwined into the day to day life of Aunty Patsy and her people and how knowledge is passed from older family members to the younger generation. Aunty Patsy and Lisa Kennedy have a poignant shared dedication at the beginning of the book to their children’s children and this is at the heart of this story, passing on stories, the connection to Country and knowledge from the past to all children.

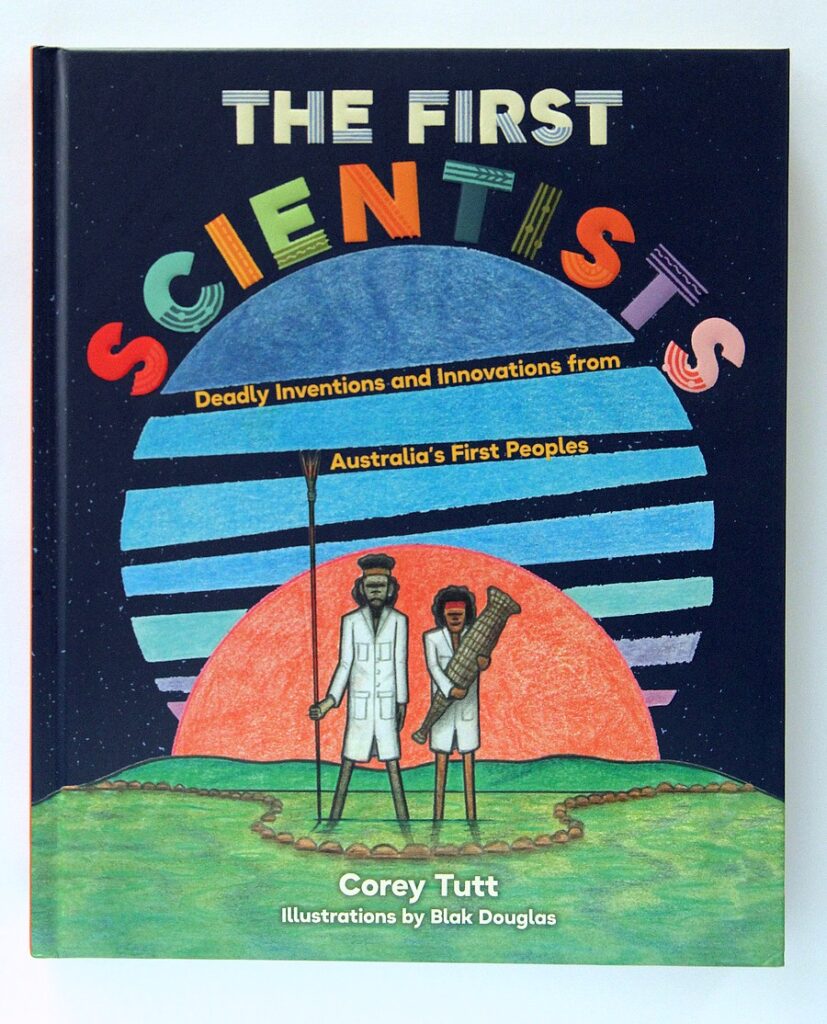

The First Scientists – Deadly Inventions and Innovations from Australia’s First Peoples by Corey Tutt, STEM advocate and founder of Deadly Science and illustrated by Blak Douglas shares Australia’s First peoples awe inspiring scientific knowledge and experience. We are privileged to be able to learn from the oldest continuing culture on earth. This book written in consultation with communities and elders is brimming with fascinating scientific facts, incredible innovation, resourcefulness, examples of problem solving and finding creative as well as effective solutions to problems through observation and skill. At the beginning of the book, Corey Tutt invites readers to follow in the footsteps of First Nations scientists and observe, pause to consider and explore what is happening in nature, notice subtle changes and details, ask curious questions, challenge the narrative and create your own. There are six chapters – the first astronomers, the first engineers, the first forensic scientists, the first chemists, the first land managers and the first ecologists. Various examples are noted throughout the book where today’s scientists are increasingly connecting with First Nations scientists to employ methods based on ancient knowledge and experience to preserve and protect the environment.

Right from the first chapter about the first astronomers, the reader will be captivated by the scientific skill and knowledge the First Nations scientists possess. There are fascinating details about how the constellations are filled with clues, the ways in which the changing positions of the constellations provide information about the seasons and inform when emu eggs can be collected. Stars can be used to gain information for hunting and harvesting. It is engrossing to read the multitude of ways the sky is used to predict weather; I was particularly fascinated to learn the observations about the points of the ends of the crescent moon and what this means for rainfall. These astute observations result in optimal conditions for harvesting and food supplies. It is enthralling to learn about some of the first scientists engineering feats, not only remarkable and complex in design (for example, the fish and eel traps) but also insightful in their planning and includes sustainable features. The skincare, bush medicine and wound treatment information is incredible, I was particularly impressed with the ingenious method used to catch fish minus fishing rods (or a fishing trap) involving a bush medicine.

Today, the wealth of knowledge and experience from the first scientists is being tapped into and used for a plethora of reasons. Scientists today are using the first scientist’s knowledge to reduce the effects of climate change. There is a story in the book about scientists from the University of Queensland collaborating with traditional owners to produce friendly glues and plastics as well as renewable, sustainable materials from spinifex grass. Rescuers use First Nations people as trackers as their expertise is invaluable in finding people and animals lost in the bush. Trackers have been used to locate crocodiles posing a threat to humans. First Nations rangers are working with scientists to save the bilby. The recent 2020 bushfires led to conversations about the ways in which the first scientists managed the land with fire. The first scientists have a history spanning over 65 000 years of managing the land with fire, this has resulted in an unrivalled knowledge and expertise in terms of timing (in which seasons and how the time of day affects the cool burns) and for regeneration purposes. The information included about the time since colonisation explores the deeply disturbing and devastating impacts of fire since ancient practices have been disregarded.

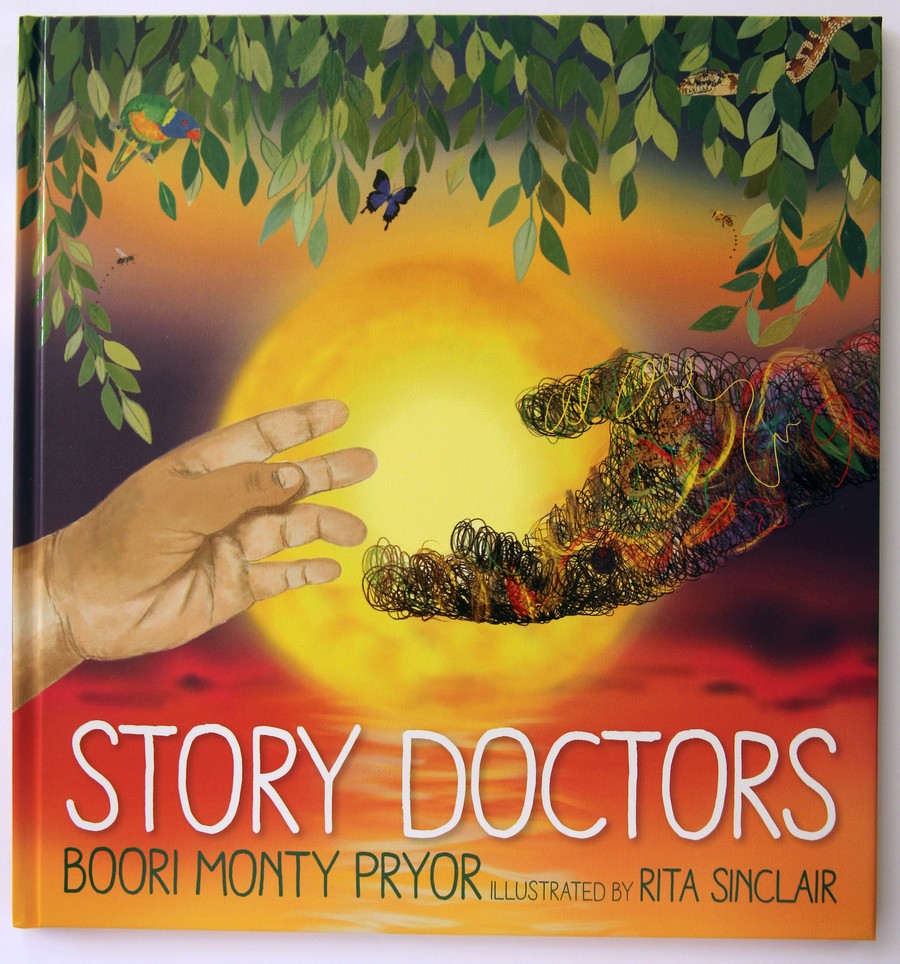

Story Doctors by esteemed storyteller Boori Monty Pryor with sublime illustrations by Rita Sinclair is a powerful and evocative story, it is an invitation to learn more about Australia’s true history, it is a celebration of the healing power of nature and the potential for infinite possibilities contained in our land. It is a story of hope, hope for Australia and its future, hope for the abundant wisdom, knowledge, innovation and experience of First Nations peoples to be included in the history books, hope for a new way of learning – learning from First Nations peoples and hope for unity. This book highlights the power of story, as a form of connection which can educate and inform. This knowledge is what is necessary for healing to occur.

The front cover is mesmerising and includes details relating to central themes in the story. There are two hands reaching towards each other – one white and the other appears to be formed from string. Boori Monty Pryor explained in an interview that this hand represents DNA from the past. Entwined in this are animals, foods and plant species. The string appears throughout the story, often in the form of a person, it carries the story and unravels the past. It represents each of us. There are also symbols of reconciliation on the cover, of two cultures coming together sharing a land. The astute reader will be able to identify a native bee and a European bee, such nuanced details occur throughout the story where the Australian native animals have been included to represent First Nations peoples and the introduced animals represent the invading Europeans as they came to Australia and call this country home.

This story is written in verse and begins with footprints created from string creating a track in the land, this is an invitation to see and learn about Australia’s past. This symbolises the beginning a journey, acquiring knowledge, making observations from the artwork created by First Nations peoples, observing the cultural practices of First Nations peoples and their connection to the land. The story causes the reader to pause to consider the impact of the arrival of the Europeans. There is a glorious double page spread of the land with native animals. It is vibrant, peaceful, harmonious and there is an abundance of life, pristine water, lush trees. There is evidence of sustainable practices with the fish trap and a plentiful supply of berries. The following page features the same landscape but deftly shows the consequences of invasion. The animals are different, introduced animals are featured and the landscape is in stark contrast to the previous page. The natural flow of the water course has now been interrupted by Europeans by damming with boulders. Trees have been cleared, fences erected, the land is not as lush and more barren. The animals appear overfed as they are all seen grazing from the land. The land is parched and cracked.

The verse invites readers to listen to the stories, observe the experiences, knowledge and culture spanning 80 000+ years and explores the remedies for unity and healing which exist in the stories. There is an extraordinary illustration which Boori has dubbed ‘the apple peel’ and it is a micro scene of one of the threads of the DNA strand. It details some key parts in Australia’s history. The story ends with seven illustrations, each symbolic of hope. This verse challenges us to come together as one, embrace inclusivity, connect with the stories and contribute to the healing. This book demands to be revisited to discover the many nuances in the illustrations as well as the text.

A QR code is included at the beginning of the book. This can be scanned to hear Boori read the book in Kunggandji and English.

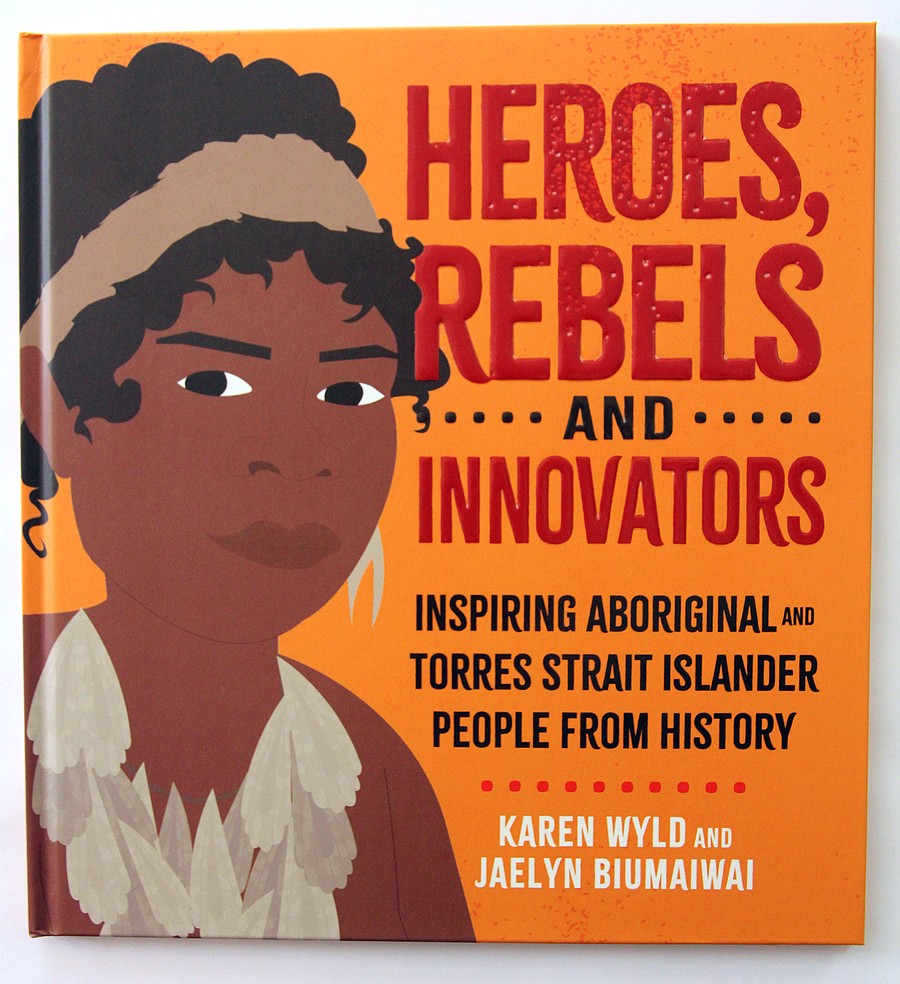

Heroes, Rebels and Innovators: Inspiring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People from History by Karen Wyld and illustrated by Jaelyn Biumaiwai contains seven powerful and engaging stories about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men and women from the early contact era. Each story is told in two parts. The first is lyrical (written in verses, consisting of four lines per verse) and brings each story to life as it is an imagining of each person’s story (based on research) and the second part unpacks the factual information.

These are stories about courage, sharing Indigenous knowledge, resilience, tenacity, displays of human strength of mind and body, defying the odds through sheer determination, selflessness, innovators and inventiveness.

Karen Wyld mentions in the Author’s Notes at the back of the book that as well as consulting archival material she also liaised with communities and organisations to corroborate the sources. Any information that had a question of accuracy was not included. The research process was extensive and time consuming to honour the people in the book as well as people’s ancestors and communities.

The simplistic illustrations complement the stories and enable the reader to visualise each person’s actions and/or achievements and connect with each story.

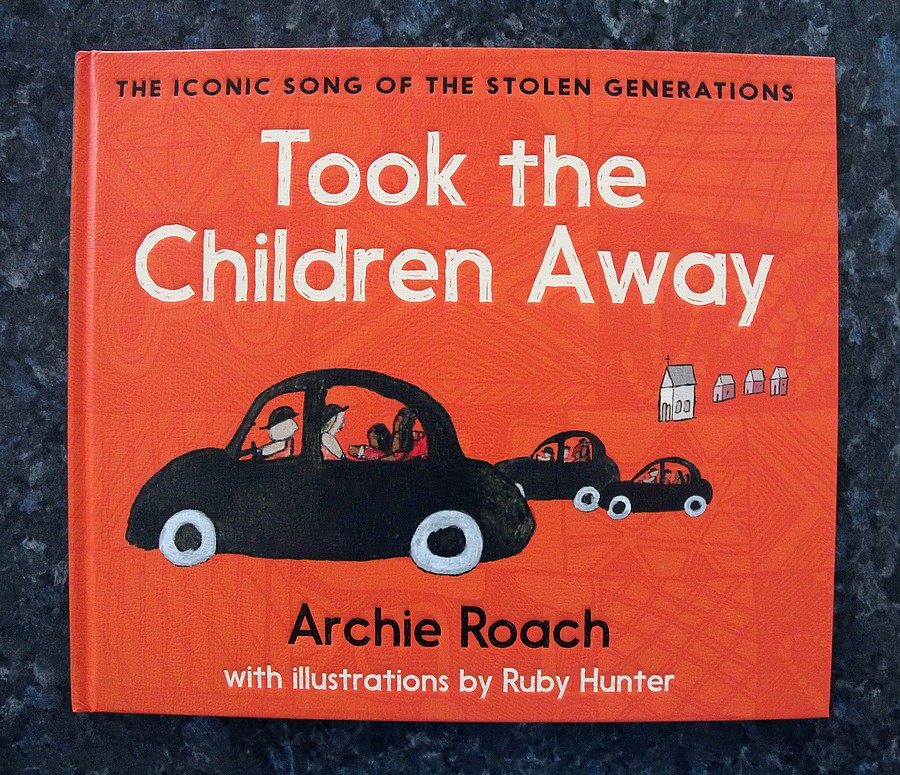

Took the Children Away by Archie Roach and illustrated by Ruby Hunter is the iconic and deeply personal song written by Archie Roach for his debut album, Charcoal Lane. This picture book has been published to honour the 30th anniversary of the song, the first ever song to receive an Australian Human Rights award. This powerful song is the story of Archie Roach and other First Nations Peoples who are part of the Stolen Generations. Archie Roach was taken from his Mum and Dad when he was two years old. He has little memory from when he was two, but his Uncle Banjo could vividly recall this time and encouraged Archie Roach to tell his story about being taken from his home in the form of a song. The evocative illustrations in the book are by Ruby Hunter, the beloved life partner of Archie Roach for thirty- eight years, also part of the Stolen Generations. Ruby passed away in 2010. Together, they produced this picture book which gives people a deeper understanding of Australia’s true and whole history. This story explores themes of loss, grief, separation, disconnection as well as reconnection, togetherness and returning home. The book also contains rare historical and personal photographs of Archie and Ruby.

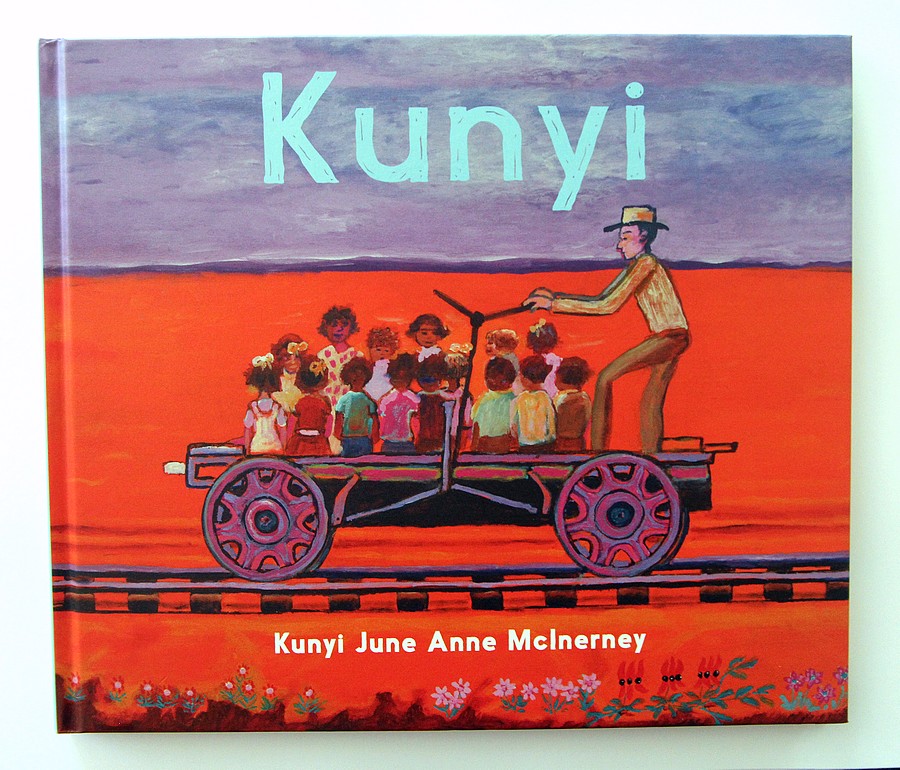

Kunyi by Kunyi June Anne McInerney tells her story in this picture book about being forcibly removed from her family and home when she was four years old to live with the missionaries at the Oodnadatta Children’s Home in the 1950s. This is a story of dispossession, loss, fear, courage, resilience and friendship. Kunyi tells this story through a written account, detailing her experiences of what it was like living at the Children’s Home and includes her vibrant art to illustrate these memories. Over sixty of Kunyi’s paintings are included in this book that were part of the ‘My Paintings Speak for Me’ exhibition.

Kunyi begins her story with her family – her mother, granny and siblings. Together, they peacefully and happily lived in a humpy where they spoke the Yankunytjatjara language.

Kunyi explains that when she went to the Oodnadatta Children’s Home her name was changed to ‘Anne’ and she was told to speak English. The home was rudimentary and lacking any creature comforts. There was no insulation, given it was in the desert, it was unbearably hot in the summer and freezing cold in winter. There was no dining room, the children ate out on the verandah under a corrugated iron roof. The children slept on beds covered in sets of rags, no sheets, just rags. Clean bath water was unheard of as all children bathed in the same, unchanged bathwater. They knew no different. There was no toilet paper, pieces of newspaper were used.

Kunyi shares her recollection of the children working in silence as their job was to peel the vegetables. She talks about the older children taunting the younger children by telling them about Mamu (bad spirits) while they ate their dinner on the dark verandah. Kunyi mentions the compulsory Bible lessons where harsh punishments were given if it was deemed you were not paying attention. As there were no toys or games for the children to play with, they employed their creativity and resourcefulness to make their own. Treasure came in the form of broken crockery, especially the ones featuring beautiful designs and these were hidden away from the Sisters. There were some treasured times too when the children would look for animal bones and suck the bone marrow, or go swimming at Hookey’s Hole. Kunyi’s artworks deftly capture the freedom and joy the children experienced when they were away from the home and swimming, walking along the gibber stones or admiring the wildflowers and eating bush tucker. Their admiration for the land and profound connection to it is palpable in the artwork. Kunyi talks about the harsh and cruel punishments and how the children were highly controlled and frequently punished. The final parts of her story tell how Kunyi came to leave the children’s home at age nine, after five years of being there, it was cruel, deceitful and done without care or compassion. Kunyi was sent away to a foster family who changed her name to June. Kunyi then shares a little about her mother’s heartbreaking story. There are personal photos from Kunyi’s private collection of her and her siblings at the home and later in life that have been included at the back of the book.

The end papers are truly a sight to behold, they feature a montage containing a piece from each of the paintings in the book. Each artwork represents a memory or experience, one part of Kunyi’s story. The endpapers resemble a classic squares quilt with each square a piece of Kunyi’s heart and story.

Kunyi’s story about the way the children in the home were torn away from their families, stripped of their identities, forced to reject their culture and adopt a white culture, often enduring harsh punishments in a highly controlled environment, have been shared so people can learn what happened and so the children’s experiences while at the Oodnadatta Children’s Home will not be forgotten. Kunyi has opened her heart to tell her story and that of the children in the home to educate and inform others about the long-lasting intergenerational impact of the Stolen Generations.

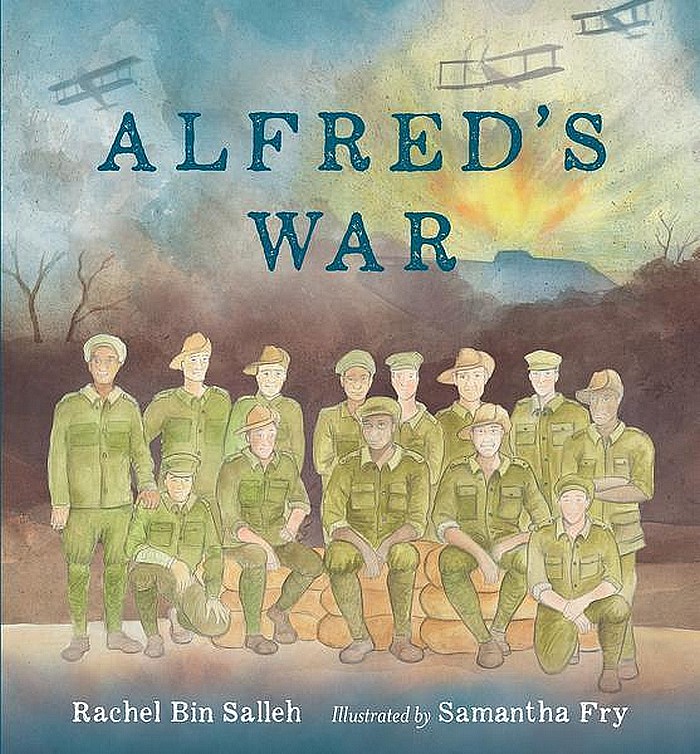

Alfred’s War by Rachel Bin Sellah and illustrated by Samantha Fry tells is a confronting story about Alfred George, an Indigenous Australian who courageously and selflessly served in WWI and returned home injured. The story explores through an Indigenous lens the effects the war had on Alfred’s physical health as well as his emotional well-being. Alfred was plagued by the horrendous memories of the war, he never forgot the men he fought alongside and the fallen soldiers, he suffered terrible nightmares and days where his overwhelming sadness was debilitating. This story importantly highlights the lack of recognition Indigenous soldiers received when they returned home, unlike the non-Indigenous soldiers who were recognised and honoured for their service. This story, in a non-biased way awakens the reader to the discrimination Indigenous soldiers experienced when they returned home and the glaring omission of celebrating their service and honouring their sacrifices. The illustrations heartbreakingly capture Alfred’s life of solitude and sadness, but also the camaraderie the soldiers shared, regardless of their skin colour and the equality Alfred experienced while serving. This story could serve as a gateway to vital conversations about the service and contribution made by Indigenous soldiers and the shameful history Australia has with this. This story raises children’s awareness of why Indigenous soldiers must be honoured and never forgotten

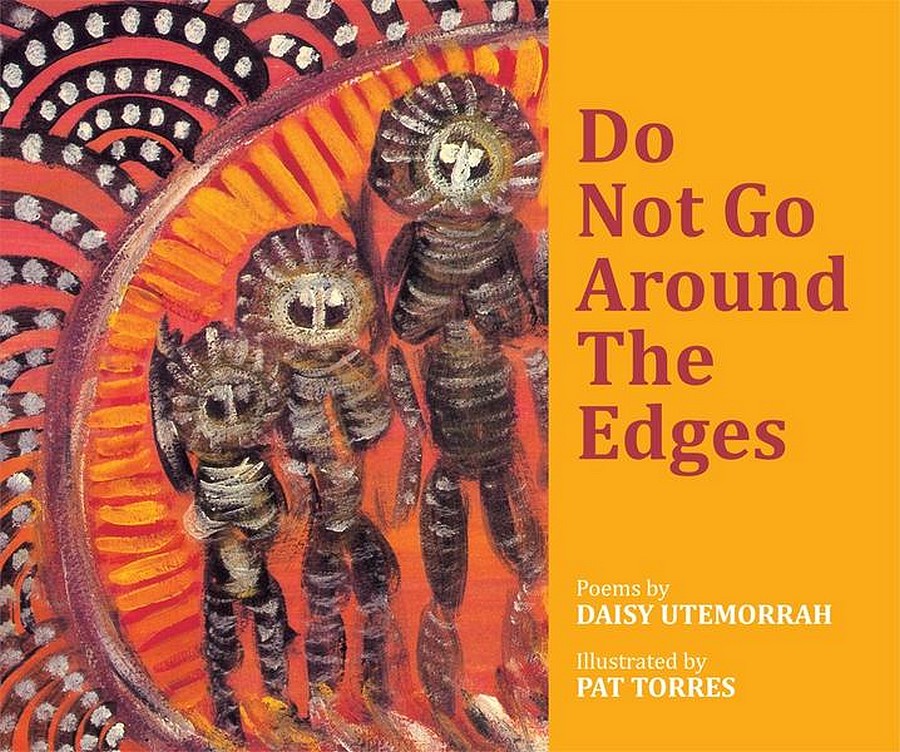

Do Not Go around the Edges by Daisy Utemorrah is an autobiographical story containing a collection of poems which explore themes relating to creation, tradition, family and country. On the bottom of the pages is the story of Daisy Utemorrah’s life and then on each page is a poem accompanied by traditional dot form artwork or contemporary images that relates to Daisy Utemorrah’s life story.

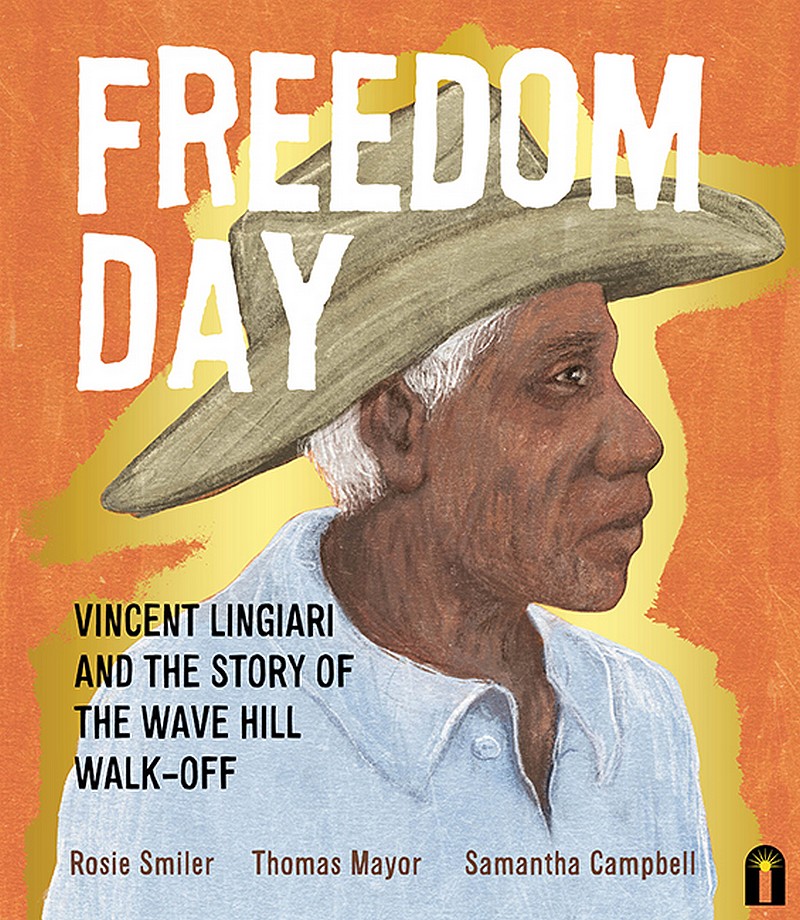

Freedom Day: Vincent Lingiari and the Story of the Wave Hill Walk Off by Rosie Smiler, Thomas Mayor and illustrated by Samantha Campbell tells the story about incredibly brave and courageous actions that became the catalyst for change and for Aboriginal people having their rights to their stolen land recognised. This is a story about one Gurindji man, Vincent Lingiari, leading over two hundred Gurindji people to make a difference.

In this book, co-author Rosie Smiler tells the story of her courageous grandfather, Vincent Lingiari and the Gurindji people. She begins the story with her family’s ancestors and tells of how they lived pre 1879 in peace and harmony with the land, a time where there was abundance. In 1879, the Gurindji people were confronted with a sight they had never witnessed before, a kartiya (white person), Nat Buchanan, on horseback. He left only to return several years later with his family and hundreds of cattle. The government had granted a large parcel of Gurindji land to Buchanan to build cattle stations. Buchanan’s presence caused life for the Gurindji people to irrevocably change. The environment suffered devastating effects, as thriving green lands were reduced to barren areas due to the number of introduced cattle trampling on the land and eating the grass. Complete disregard was shown to sacred sites and access to meeting places, hunting grounds and waterways was denied. Aboriginal people were massacred and the Aboriginal population significantly declined.

During this time, many men were captured and enslaved, working sixteen hour days of gruelling hard labour. No wages were paid to the Aboriginal workers, instead only meagre rations. While this is confronting to read, this is Australia’s true history.

The next part of the story in this picture book is about hope as Rosie shares what her grandfather achieved. Vincent Lingiari saw a desperate need and responded courageously. He spoke to the kartiya about the inadequate payment for his people. Empty promises were made by the kartiya. These obstacles did not stop Lingiari as he organised with his people to protest and walk off the cattle station.

In a turn of events, Lingiari found allies in a kartiya who worked on the wharves and two Aboriginal men from the union who agreed to support the Gurindji people if they proceeded with the strike.

Lingiari spoke to the station manager informing him that Aboriginal people will no longer work for no pay and that they intended to walk off. On August 23, 1966 Vincent Lingiari led more than two hundred courageous Aboriginal people as together they walked off Wave Hill Station. They walked for sixteen kilometres, laden with their belongings and some carrying their children. There were attempts to intimidate the Aboriginal people, but Vincent Lingiari was a resolute leader and the people were inspired to follow him and continue walking despite the intense heat, their need for water and their sheer exhaustion. When they reached their destination which was the last remaining small area of land not owned by the British, the Aboriginal people set up camp and remained there for two weeks until their allies who had agreed to help them arrived.

For nearly a decade the protest continued. In this time discussions were had, conversations were started and the iconic moment when Prime Minister Gough Whitlam picked up a handful of the Gurindji’s peoples land and poured the sand back into Vincent Lingiari’s hand occurred.

The story ends with the strong message that there is still unfinished business, while the Aboriginal people have some of their land back, the government makes decisions and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aren’t able to influence these decisions in Canberra. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people still need a constitutionally enshrined Voice. The final page ends with a powerful rallying call to action.

After the story there is fascinating information and photographs about Freedom Day – the Festival.